BLOG ENTRY 3

Design Theory of Murcia City Hall Annex

By Ian Mesa | 12/20/24

Now, let's dive deeper into Moneo's thought process and examine how he approached the design of the Murcia Town Hall Extension.

CONTEXTUALISM

Rafael Moneo’s design approach is often regarded as a model for seamlessly connecting the old and the new within the urban fabric. As noted in Sennott’s Encyclopedia of 20th Century Architecture (2004), Moneo’s work showcases his ability to bridge the divide between urban design and architecture. Sennott draws parallels between Moneo’s approach and the challenges of rebuilding Beirut’s city center after successive world wars, emphasizing Moneo’s success where many architects struggled. Through contextualism—designing buildings that respect historical contexts while contributing to the evolution of the urban landscape (Sennott, 2004)—Moneo challenges the traditional divide between these disciplines, offering a thoughtful and integrated response to complex urban issues.

CONTINUITY AND RHYTHM

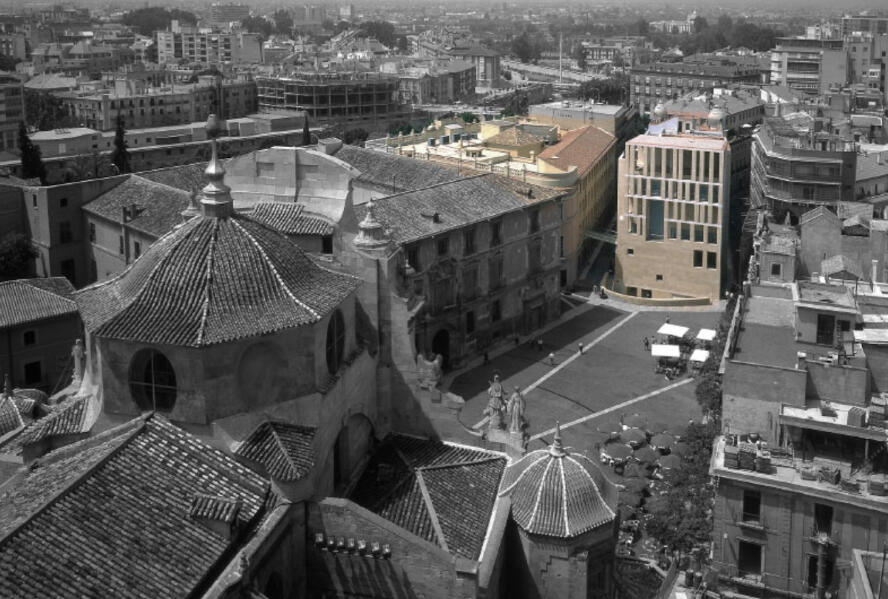

The Murcia Town Hall Extension by Rafael Moneo also exhibits the principle of architectural continuity, where the new intervention responds to the historic context without imitating it. Situated adjacent to Murcia’s Baroque Cathedral , Moneo designed the extension as a subdued yet complementary structure, ensuring that it does not overpower the grandeur of the existing architecture. Moneo’s work is also an example of how architecture can respond not only to the immediate needs of its occupants but also to the larger urban context.With its transparent surfaces and the use of traditional materials like stone, the building not only connects with the city’s historic fabric but also stands as a distinct and modern civic symbol.

CIVIC SPACE AND ARCHITECTURAL FORM

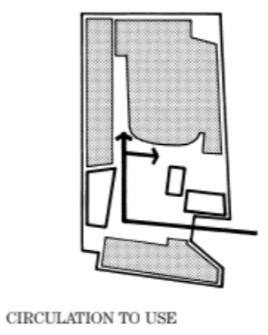

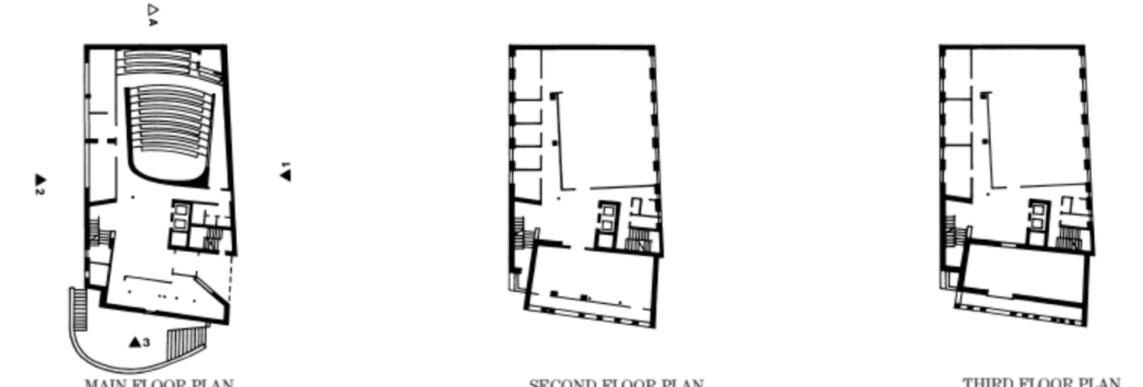

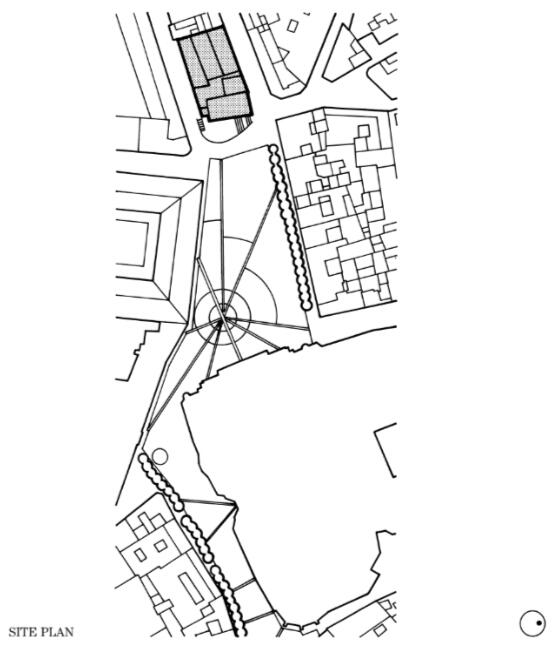

At the core of the design theory is the idea of civic space. The extension was designed as a response to the needs of the expanding municipality, but it also serves as an important statement in the historical urban fabric of Murcia. The existing Town Hall building, a neoclassical structure, set the stage for the new addition. Moneo's design respects this legacy by incorporating classical elements—such as columns, proportions, and symmetry—into the new building's form but with a contemporary reinterpretation. Moneo’s commitment to making the Town Hall a space for public interaction, both physically and symbolically, he prioritized the creation of the public courtyard, located at the back part of the town hall, as a central feature of the design, providing a gathering space for citizens. The transparency of the building’s facades, which invites the public to engage with the building’s activities and functions. Moneo’s careful consideration of spatial organization ensures that the building does not just serve as a place of administration but as a living part of the urban environment.

MATERIALITY, PROPORTION, AND MODERNITY

Moneo’s approach focused on designing a building that harmonizes with its surroundings through thoughtful material choices and proportion, rather than relying on eclectic styles or ornamentation. The extension is carefully positioned within the city’s historic grid, with its form and massing respecting the scale of nearby buildings while making a modern architectural statement. By using sandstone, a material that echoes the texture and color of the Cathedral, Moneo ensures the extension connects with the city’s historic context while also standing as a distinct, modern civic symbol. This approach reflects Alvar Aalto’s philosophy of creating buildings that are both poetic and accessible. Moneo’s design exemplifies Aalto’s influence, balancing contemporary aesthetics with a deep respect for historical context, fostering a dialogue between the past and the present (Frampton, 2007).

SYMMETRICAL FENESTRATION

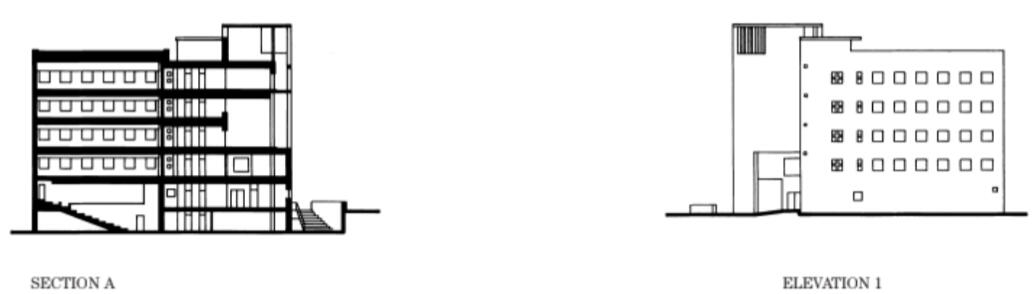

Moneo’s design brings a sense of balance and harmony to the building through its carefully considered fenestration. Drawing inspiration from the classical architecture of the original Town Hall and the nearby Baroque structures, the windows are arranged thoughtfully, both horizontally and vertically. This arrangement creates a sense of order while respecting the natural rhythm of the building. The proportions of the windows, in terms of height and width, are carefully matched to the scale of the building, allowing the extension to blend seamlessly with its surroundings.Though the design follows a clear pattern, it avoids feeling too repetitive. Moneo introduces subtle variations in the size and proportion of the windows on different levels, giving the building a sense of individuality while maintaining overall symmetry. This approach adds depth and interest to the facade, offering a modern twist on classical principles without losing the sense of balance.

A BALANCE BETWEEN UTILITY AND AESTHETICS

Vitruvian Principles of utilitas (function), venustas (beauty), and firmitas (durability) are clearly embodied in the Town Hall Extension. Moneo’s design prioritizes functionality by ensuring the extension serves the needs of the growing municipality. The building is designed to accommodate both administrative activities and public access, providing efficient workspaces for government employees and welcoming public areas.

The principle of venustas, or beauty, is evident in the building’s aesthetic harmony with its surroundings. As discussed earlier, the materiality or usage of sandstone and glass creates an architectural connection with the surrounding historical styles all while reflecting the transparency and openness of modern governance. The patterns used for fenestration and proportionality contribute to the rhythmic visual interest while maintaining a sense of order.

Moneo also emphasizes firmitas by selecting durable materials that ensure the building's longevity and structural integrity. These material choices not only contribute to the aesthetic appeal but also ensure the building’s resilience against the test of time, reinforcing the durability and functional strength of the structure.

BLOG ENTRY 4

Discursive Analysis of Murcia City Hall Annex

By Janine Asinas | 12/20/24

Spain’s architectural trajectory during General Francisco Franco’s regime (1939–1975) was shaped by authoritarian preferences for neoclassical and vernacular styles, while modernist movements were suppressed due to their association with leftist ideologies. Avant-garde architects either fled into exile or conformed to state doctrines. This period of architectural stagnation gave way to revitalization after Franco’s death in 1975 and the subsequent transition to democracy. The adoption of the 1978 Spanish Constitution marked a turning point, fostering regional autonomy and cultural resurgence. Spain’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1986 further bolstered modernization efforts, enabling urban renewal projects and a reimagining of public spaces.By the 1990s, Spain had stabilized politically and economically, ushering in an era of architectural experimentation rooted in regional identity. Architects such as Oriol Bohigas championed a balance between modernity and historical memory, emphasizing localized urban interventions over sweeping transformations. This approach reflected a growing discourse on the role of architecture in preserving cultural heritage while addressing contemporary needs. Rafael Moneo, as a key figure of this period, embodied these principles in his designs, notably in the City Hall of Murcia.The City Hall annex engages directly with the surrounding historical fabric of the Plaza del Cardenal Belluga. This urban square is defined by two dominant baroque structures: the Murcia Cathedral and the Episcopal Palace. Moneo’s intervention—a restrained modernist volume—bridges the gap between these architectural icons without imitating their ornate styles. The choice of brick and native sandstone as the primary material establishes a visual dialogue with the cathedral’s façade, ensuring that the new structure complements rather than competes with its neighbors. This materiality underscores a commitment to continuity, demonstrating sensitivity to the cultural and historical significance of the site.The annex’s minimalist geometry reflects Moneo’s modernist ethos, emphasizing clean lines and functional spaces. However, this simplicity is not devoid of meaning; instead, it serves as a counterpoint to the elaborate baroque surroundings. The building’s design navigates the tension between tradition and innovation, offering a contemporary reinterpretation of civic architecture that aligns with the democratic values of post-Francoist Spain. Its understated elegance challenges the notion that modern architecture must be visually dominant to assert its presence, instead opting for subtle integration into the existing urban environment.Moneo’s annex can be read as a response to the postmodern condition, grappling with the erosion of historical reference in modernist architecture. Situated in a historically significant site, Moneo ensures that the new structure neither overpowers nor threatens the existing buildings. Through this thoughtful approach, he initiates a critical dialogue on the role of civic architecture in a democratic society. The design embodies transparency and functionality, reflecting the ideals of accessibility and public service. This approach contrasts with the monumentalism of Francoist architecture, which often prioritized ideological expression over user-centered design.The building’s spatial organization further reinforces its civic identity. Internally, the annex prioritizes functionality and clarity, aligning with the needs of a modern municipal government. Externally, its presence enriches the urban surroundings without overshadowing the cathedral or palace, maintaining the plaza’s historical significance as a communal space. This careful calibration of scale and proportion exemplifies Moneo’s mastery in creating architecture that respects its context while asserting its modern day relevance.The City Hall of Murcia exemplifies a broader cultural shift in late 20th-century Spanish architecture. Following decades of authoritarian rule, architects were tasked with redefining national identity through the built environment. Moneo’s work reflects this mandate by synthesizing historical awareness with modernist principles, offering a model for how architecture can engage with history without resorting to pastiche.The annex’s design also resonates with Spain’s regionalist aesthetic, a movement that emerged in the post-Franco era as a counterpoint to the homogenizing tendencies of modernism. By incorporating local materials and responding to the specificities of its urban context, Moneo’s building asserts the importance of place-based design in an increasingly globalized architectural discourse. This emphasis on regional identity aligns with the principles championed by Barcelona’s Group R in the 1950s and later expanded upon by figures like Bohigas during the city’s Olympic-led transformation in the 1990s.While the City Hall annex has been widely praised for its sensitivity to context and understated elegance, it is not without critique. Some might argue that its minimalist design risks being perceived as overly deferential, lacking the boldness or assertiveness often associated with modern civic architecture. Others might question whether its restraint adequately addresses the evolving demands of urban spaces in the 21st century. However, these critiques also highlight the building’s strength: its ability to provoke meaningful dialogue on the role of architecture in mediating between past and present.Ultimately, Rafael Moneo’s City Hall of Murcia represents a masterful negotiation of historical continuity and architectural innovation. Its design reflects the broader cultural and political transformations of post-Francoist Spain, offering a thoughtful and contextually responsive approach to civic architecture. By harmonizing modernist principles with the baroque beauty of its surroundings, the annex not only enriches the urban landscape of Murcia but also contributes to the ongoing discourse on the relationship between architecture, history, and identity.

BLOG ENTRY 5

Conclusion

By Ian Mesa | 12/20/24

In conclusion, designing something new in a place so steeped in the past requires a delicate balance between respect for historical context and the introduction of modernity. Rafael Moneo’s design for the Murcia City Hall Annex hopes to demonstrate that respect for what already exists is no obstacle for freedom in architecture. Moneo’s City Hall of Murcia Annex stands as a timeless dialogue between architecture and history—anchored in the present, reverent of the past, and envisioning a future where design continues to bridge cultural legacy with contemporary innovation.This project also has a notable impact on contemporary architecture by exemplifying how modern design can thoughtfully engage with historical contexts. Similar to the works of architects such as Tadao Ando, and even the heritage conservation projects in the Philippines such as the Diplomat Conservation Project of Prof. Lico in Baguio City, Moneo's approach reflects a growing trend in architecture where the preservation of heritage and the exploration of modernity are integrated.

REFERENCES

Clarke, H. & Pause, M. (2012). Precedents in Architecture: Analytic Diagrams, Formative Ideas, and Partis. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Eisenman, P. (1976). Post-Functionalism, Oppositions, 6. pp. i–iv; later reprinted in P. Eisenman, Inside Out: Selected Writings 1963—1988 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2004), pp.83–87.

Frampton, K. (2007). The Evolution of the 20th Century Architecture. Springer-Verlag/Wien and China Architecture & Building Press.

Sennott, R. S. (2004). Encyclopedia of 20th century architecture (Vol. 1). Fitzroy Dearborn.

Wittkower, R. (1962). Architectural principles in the age of humanism. [3d rev. ed.] New York, Norton.